SOLID Must Die: A No-BS Guide to Simple, Scalable Code

SOLID Must Die: A No-BS Guide to Simple, Scalable Code

by Ron ChanOu

Part 1: Cost-Based Management

“Something I have noticed as juniors become intermediate, and as intermediate become seniors”

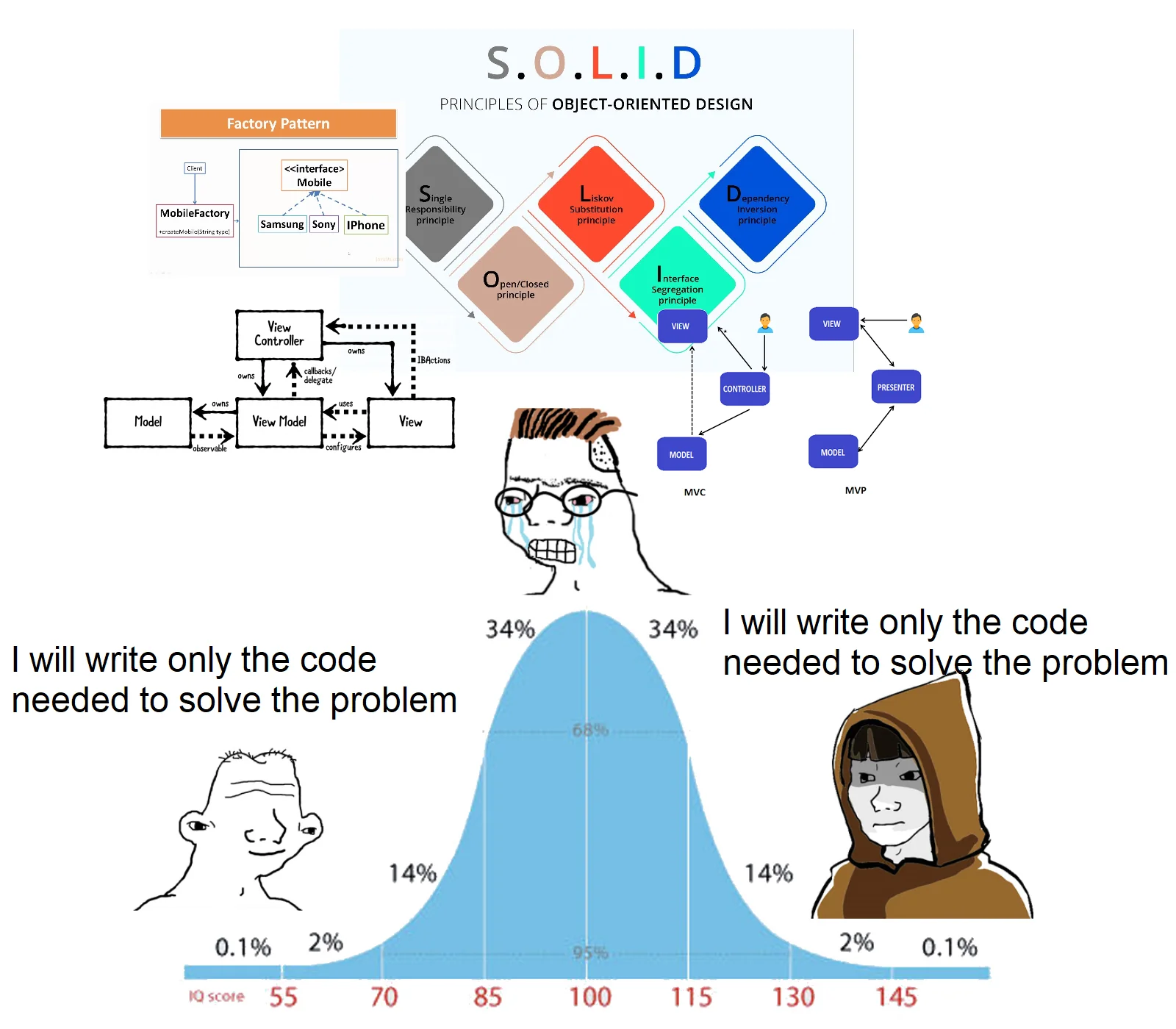

– meme posted by PM_ME_LECTURE_NOTES

“Something I have noticed as juniors become intermediate, and as intermediate become seniors”

– meme posted by PM_ME_LECTURE_NOTES

Background

SOLID is scalability theatre. Objects are fine, but the doctrine of Object-_Orientation_ . Have you ever read the children’s story of Stone Soup? That’s the extent to which Object-Oriented Programming “works”: a placebo to get fresh programmers thinking about how they can design their programs, beyond copy-pasting a bunch of crap everywhere.

Some of us eventually learn we don’t need the OOP stone, and ditch it. Others still feel the need to put stones in their soup, and carry these heavy stones around with them everywhere. They might even refuse to eat soup served without a stone. They’ll get into heated debates about what types of stones make the best soup: some argue for soft, rounded pumice, others for sharp obsidian. Some say we should even use little rocks that we eat with the soup because that’s what birds do, and we need to model the way we cook our soup after nature. They’ll tell you it’s painful at first, but promise one day it’ll just click, and you’ll wonder how you ever lived without eating and sh!tting rocks in the first place.

Personally, I never bought into SOLID and the like, but I did go through a Functional Programming phase. To get what I went through, just replace the OOP diagrams in the meme above with concepts like higher-order functions, currying, “composability”, declarative DSLs, homoiconicity, provable correctness, and algebraic effects.

These are all compelling techniques that sound cool in a vacuum. In practice, they are far too overused and most of them do not pay off, because they all have drawbacks which usually aren’t mentioned (or even noticed) when they are first proposed. I could write several articles discussing the specific pros and cons of each of these ideas, but for now, I’ll just say that they tend to cause excessive fragmentation, increased mental overloading, unnecessary ambiguity, premature ossification and reduced flexibility…while not actually solving any hard problems that actually matter.

Bad programmers worry about the code. Good programmers worry about data structures and their relationships.

– Linus Torvalds

Yes, writing good software is a nuanced art that takes lots of practice. However, I think there are a handful of simple, yet very helpful techniques that most resources overlook. I have seen others touch upon these ideas, but none in the clear, satisfying detail that I would like. That is why I am writing this series: to serve as the no-nonsense guidebook that I wish I had when I first began my programming career.

I’ve recently used the methods I will describe with great success, on a codebase I inherited from my old lead when he left a few years ago. He and another old colleague of mine were smart guys who definitely knew a lot, and I wouldn’t be where I am today without them. But by that nature, they also had a tendency to over-engineer with modern, “hip” practices: Separate packages that didn’t really need to be split into separate packages. Multiple services that communicated to each other via a separate PubSub service, for internal business applications that didn’t really need them at all. Code full of builders and providers that accepted other builders and providers as parameters. A good portion of the code might appear readable and elegant to a non-technical outsider, with loads of method chains like:

InitProcessingProvider(db).LoadFromOrderBuilder(ob).LoadRelatedRecords().

DownloadAllFiles().ProcessStandardFiles().ProcessCustomFiles().

UploadAllFiles().OnSuccess(SaveOrder)

Wow, so clean, it feels more like reading English instead of code! Isn’t that cool?

Well, despite all that sophistication, I could tell from the Slack messages that our users weren’t very satisfied with the system. Soon after I took over, I learned just how buggy and broken it was: it had gotten bad enough that, in order to work around its failure points, our users were maintaining their own auxiliary Google Sheets and sending each other emails. And yes, the codebase did have automated tests, though I can’t say exactly how useful they were. They clearly weren’t enough, and they didn’t help me all that much.

So I got to work making sense of the code, squashing bugs and implementing feature requests using a much more straightforward approach. Within a few months, I had turned things around significantly. Eventually, my boss told me (I’m paraphrasing): “Before, management was bashing the system. Now they’re praising it. Now they want to consolidate orders from the other systems into your system.”

Ah, rewarding good work with more work, classic. Well, at least working with the codebase also sucked less, as I gradually refactored the legacy logic and slotted in a more practical testing framework. Both the users were happier, and I was happier.

The psychological benefits of this approach cannot be overstated. Writing and especially reading excessively abstracted, dependency-inverted code may have gotten easier for me, but it never got any less mentally fatiguing. It’s just as annoying to wade through this type of code now, as it was when I first tried to “get” Angular and Ninject 12 years ago.

I have no doubt these paradigms are pushing many smart individuals out of or away from software development. I can say this because I was at the brink myself. In fact, the cynic in me would say that this is the ulterior motive for all these paradigms…but I won’t get into that.

Some of you might say use the right tool for the right job, etc.

That is a failing of the paradigm. Aspirational

[balance and productivity]

I’m Not Alone

My experience is not an isolated one. Below are some YouTube videos by engineers more knowledgable than myself, who have inspired and affirmed my current programming philosophy. If you’re too busy to watch these, I recommend at least listening to them while you’re working or doing chores.

Object-Oriented Programming is Bad/Embarrassing/Garbage: a three-part series by Brian Will. In part 1, he outlines his case against OOP; in part 2, he critiques four OOP snippets; and in part 3, he rewrites a large OOP codebase.

ttstrtsr

“Clean Code” is bad. What makes code “maintainable”? by Internet of Bugs, describing his experiences dealing with “Clean Code” and explaining why it’s flawed.

ttstrtsr

Shawn McGrath: OOP Rant (NSFW language): in which, with remarkable drunken lucidity, he steps through, rails against, and rewrites a convoluted object-oriented library authored by an eminent Microsoft researcher.

ttstrtsr

Solving the Right Problems for Engine Programmers by Mike Acton, a prominent advocate of Data-Oriented Design. His advice applies to other domains as well, not just engine programming.

ttstrtsr

The most important article on software development, a review of the article “Semantic Compression”, written by Casey Muratori (of Handmade Hero fame). You can read the original article yourself, here. In the video, Ted Bendixson gives an animated reading of the article, while relating it back to his own experiences and adding even more great insights.

ttstrtsr

Okay, enough ranting, let’s get to my first technique. I’m still not sure about the name, but for now I’ve settled on Cost-Based Management (CBM). I like this name precisely because it doesn’t sound overly technical, programming-specific, dogmatic or academic.

Cost-Based Management, Explained

If you look at the development process for a piece of code as a whole, you won’t overlook any hidden costs. Given a certain level of performance and quality required by the places the code gets used, beginning at its inception and ending with the last time the code is ever used by anyone for any reason, the goal is to minimize the amount of human effort it cost. This includes the time to type it in. It includes the time to debug it. It includes the time to modify it. It includes the time to adapt it for other uses. It includes any work done to other code to get it to work with this code that perhaps wouldn’t have been necessary if the code were written differently. All work on the code for its entire usable lifetime is included. – Casey Muratori, “Semantic Compression”

CBM is one of the first tools I reach for when starting work on a new app or feature, much like how an artist might sketch an outline before filling in all the details. If I had to classify this approach, I would consider it “functionally procedural”.

When writing new code, I use plain structs and plain functions the vast majority of the time. If you’ve read or watched introductory functional programming tutorials, you may have noticed that many of them start with this basic, sensible idea: separate pure functions from impure functions with side effects. However, they’ll usually leave it at that, then proceed to tell you that you should compose curried higher-order functions into elegant map/reduce/filter pipes, and then do a monadic bind or some BS like that.

To which I say: Hold up, let’s wind back a bit. There’s a lot more nuance to functions than just “pure” versus “impure”, and I’d like to delve into that. Not all side effects are created equal.

The easiest way for me to explain this is by example. So what we’ll do is review a list of Go function headers and, based only on their names and type definitions, we are going to guess other properties they might have, that aren’t captured by the types.

(For some of these, I just took Go standard library function signatures, and gave them more intuitive names.)

func Sum(addends...int) int

func Ceil(x float64) float64 // same as math.Ceil

func ToUpperCase(str string) string // same as strings.ToUpper

func PrintLine(a ...any) (int,error) // same as fmt.Println

func GetRandomInt(max int) int // same as rand.Intn

func GenerateWorldFromSeed(seed int) *World

func ConvertStringToBytes(str string) []byte

func GetSHA256Hash(str string) string

func Sleep(d Duration)

func ConvertStringToInt(string) (int, error) // same as strconv.Atoi

func ScanUserInputLine(a ...any) (int, error) // same as fmt.Scanln

func GetCurrentTimeNow() Time // same as time.Now

func GetStartOfNextHourFromNow() Time

func GetStartOfNextHour(time *Time) Time

func GenerateHashFromPassword(password []byte) ([]byte, error)

func ReadFile(name string) ([]byte, error)

func WriteFile(name string, data []byte, perm FileMode) error

func WriteTempFile(name string) error

func WriteToRotatingLog(logDir, str string) error

func SendEmail(email *Email) error

func PrepareCustomerThankYouEmail(cust *Customer, body string) *Email

func CreateDBRec(a any) error

func DeleteDBRec(a any) error

func UpdateDBRec(a any) error

func SelectQuery(a any) error

func PrepareComplexQuery(a any) (*Query, error)

func QueryOpenOrdersThenDownloadRelatedFilesThenMergeToPDFThenUpload() error

func HTTPGet(url string) (resp *Response, err error)

func HTTPPost(req *Request) (resp *Response, err error)

func FetchListOfYouTubeVideos(req *Request) (resp *Response, err error)

func ChargeCreditCard (cc *CreditCard, amount float64) error

func SendDocumentToPrinter(printer *Printer, doc *Document) error

func DestroyCity(name string) (int, error)

Ready? Here are my answers…

For each function, I wrote a code comment below with my own “cost-based” annotations, plus an explanation.

func Sum(addends...int) int

// pure

Let’s start simple. Sum has the properties of a pure function: for a given set of input parameters, it always returns the same output, and it has no side effects. It requires a CPU and RAM to run, but that’s implied for all functions; we know those requirements are met if we can run this program in the first place.

func Ceil(x float64) float64

// pure

This is also a pure function, just with different input/output types.

func ToUpperCase(str string) string

// pure

Same here, assuming this function only serves to uppercase strings.

func PrintLine(a ...any)

// effect; contained

Now we have our first side effect: printing to the terminal. It’s very low-cost; so much so that these can remain littered in code long after they are needed, without anyone noticing. Much like garbage collection for memory, you can reasonably assume that the app has a built-in means of “cleaning up” terminal lines; that is, removing the oldest ones. Thus, its costs are contained. You could almost treat this like any pure function.

func GetRandomInt(max int) int

// nondeterministic

Now we have a function that can return different outputs for multiple calls with the same input. Although running this might have a low computational cost, the nondeterminism adds a “meta-cost” that affects any human working with the code. It does so by decreasing the predictability of the output, not just for this function, but for any functions that use the output.

func GenerateWorldFromSeed(seed int) *World

// pure

If you’re into games that employ procedural generation (such as many roguelikes) you’re probably familiar with the concept of a seed: a single value that serves as an input to the game’s generation algorithm, returning the same game world for that value every time. Besides making the generation logic easier to debug for its developers, this allows players to share seeds and play the same “runs”, some of which might be particularly desirable or intriguing. Even though the generated world returned by this algorithm can be quite complex, it is still a pure function, much like the simple Sum.

This will be a recurring theme: pushing non-deterministic data and events out to the “edges” of the system, and keeping the “core” deterministic. (Note that I didn’t say “impure” and “pure” like a functional programmer; I’ll elaborate on that as we continue.)

Another way to see it: non-deterministic functions have a specific qualitative cost–they lose predictability and reproducibility. Any scientist knows that a valid experiment must be reproducible. Developers should similarly value reproducibility: highly reproducible code is highly testable and verifiable code.

func ConvertStringToBytes(str string) /*obfuscated*/ []byte

// pure

Much like the first few functions we reviewed, for a given input, this always returns the same output. However, that output has a different quality compared to what we saw before: it is not easily readable to most humans. If for some reason you wanted to unit-test this function, you likely wouldn’t be hand-writing the outputs you wish to assert. We know in our heads that the result of ToUpper(“apple”) should be “Apple”, but how many of us could say the same for ConvertStringToBytes(“apple”)?

func GetSHA256Hash(str string) /*obfuscated*/ string

// pure

Like the previous function, for a given input you wouldn’t quickly “know” or be able to handwrite the output. To put it back in cost-aware terms, the “cost” here is human readability. This might not directly affect how you use it in your code, but probably affects how you approach testing it, or any other functions that use it.

func Sleep(d Duration)

// delaying

This function is technically “pure”; in fact, it returns nothing. But it does use one important resource: time. The time cost of Sleep directly correlates with the duration passed into it.

All types of resource consumption essentially convert into two “final” costs: energy usage and time. We might care a bit about the former, but we usually care a lot more about the latter. We care to distinguish between getting data from the CPU cache, memory, disk and the network, because their access times can differ by several orders of magnitude. Game rendering has a strict time budget in order to achieve a target FPS. So, it’s important to note when a function can increase “time consumption”, even without computation (and even if that’s the desired outcome).

func ConvertStringToInt(string) (int, error)

// pure

This function attempts to convert the given string into an int. It is a pure function which returns an error for any string inputs that it cannot interpret, such as “twelve” or “12a”. It demonstrates how Go functions can return multiple return values, with the last value usually being any error that occurred while running the called function. If no error occurred, the value of error is nil. In this case, even with the additional error return value, the function remains pure, but we’ll see how this can change with other kinds of functions…

func ScanUserInputLine(a /*mutated*/...any) (int, error)

// nondeterministic; delaying; mutating effect

This waits for the user to input a line of text, then assigns that input value to the variable reference(s) passed into it. It returns the number of items successfully scanned, and any error that occurred.

Like GetRandomInt, it has a nondeterministic output. Like Sleep, it causes a delay, blocking further execution of the thread until the user enters their input.

However, unlike the previous functions, it potentially mutates the variables passed into it. For most applications, mutable state is necessary, but is a likely source of bugs. So you might want to make note of what state can be shared among multiple functions, and when that might be mutated.

This is also where consistent naming conventions help. For my own mutating functions, I commonly use a Set prefix; so for this function, I might prefer a name like SetRefsFromUserInput. Conversely, you could use a “subword” to distinguish globally shared mutable references, such as “Instance” or “Ref”.

I think experienced programmers tend to have built up a suite of keywords that they use to signal any impure effects a function might have. It’s a sort of modernized Hungarian notation that evolved to fill in the remaining gaps left by mainstream type systems.

func GetCurrentTimeNow() Time

// nondeterministic

The returned output is different for every time this is called…literally.

func GetStartOfNextHourFromNow() Time

// nondeterministic

Since this function accepts no parameters, it is implied that the calculation is based on the always-changing current time. It may very well call the nondeterministic function above, GetCurrentTimeNow. In that case, you could theoretically infer that this function itself is nondeterministic, using a sort of static “cost annotation checker” tool. Something to think about.

func GetStartOfNextHourFrom(time *Time) Time

// pure

By parameterizing the time passed into the start-of-next-hour calculation, we maintain the purity of the calculation. We have again “pushed” the source of nondeterminism to the “edge”.

func GenerateHashFromPassword(password /*sensitive*/ []byte) ([]byte, error)

// pure

This is a pure function, but with one caveat that I think is worth noting: the input value being passed in is likely sensitive data that should not be persisted. This may affect how you choose to perform logging or testing around the function.

func ReadFile(name string) ([]byte, error)

// requires: disk/filesys; contained

Here is our first function that relies on a consumable dependency besides memory. In this case, that dependency is the disk and filesystem. However, the act of running ReadFile doesn’t actually consume more of the resource itself; it simply requires it.

You can also think of the disk as an implicit parameter to ReadFile. You can expect the same output for the same input if the relevant disk state also remains the same between subsequent calls. This contrasts with GetRandomInt and GetCurrentTimeNow, which are expected to return a different, largely unpredictable result every time you call them. Even if the call results in an error because of some file issue (like lack of permissions), we expect it to return the same error for each call with that particular “invalid” disk state.

Tangent Time:

This is where you would commonly be told you should do something like isolate operations that touch the filesystem into a service dependency that you then inject into every other service that uses it. That way you can mock out the filesystem for unit-testing.

To rebut that, I’ll simply defer to another infamous programming contrarian, David Heinemeier Hansson. Here are some key quotes of his that I endorse, from his posts TDD is Dead and Test-Induced Design Damage:

Test-first fundamentalism is like abstinence-only sex ed: An unrealistic, ineffective morality campaign for self-loathing and shaming.

Test-first units leads to an overly complex web of intermediary objects and indirection in order to avoid doing anything that’s “slow”. Like hitting the database. Or file IO.

The fear of letting [tests] talk to the database is outdated. This decoupling is simply not worth it any more, even if it may once have been.

You do not let your tests drive your design, you let your design drive your tests!

Stop obsessing about unit tests, embrace backfilling of tests when you’re happy with the design, and strive for overall system clarity.

Getting back to ReadFile,

func WriteFile(name string, data []byte, perm FileMode) error

// consumes: disk/filesys; uncontained; destructive

Like ReadFile, this function requires the disk.

func WriteNewTemporaryFile(name string, data []byte, perm FileMode) error

// consumes: disk/filesys; contained; idempotent

func WriteToRotatingLog(logDir, str string) error

// consumes: disk/filesys; contained

func SendEmail(email *Email) error

// requires: network; irrevocable

func DestroyCity(name string) (int, error)

// irrevocable, destructive

This function is based on an old programming joke by OG computer scientist Nathaniel Borenstein:

It should be noted that no ethically-trained software engineer would ever consent to write a DestroyBaghdad procedure. Basic professional ethics would instead require him to write a DestroyCity procedure, to which Baghdad could be given as a parameter.

that no mainstream language has any capability to formalize the distinction between a lowly Printf and DestroyCity. Some functional languages do formalize different effects, but seem to be more concerned with control flow

In Summary…

- Organize and label your procedures by costs.

- Keep most of your logic in lower-cost procedures.

- Costs entail not just the physical resources required for a given procedure to run, but qualitative costs that affect human understanding, such as whether the output keeps or loses predictability, readability, etc.

- Ensure you have mechanisms for containing and recouping costs.

- Holistically consider and balance all costs. The ultimate costs we should minimize are our human time and energy, both for developers and especially for end-users.

Proposal: A Cost-Aware Development Tool

Show me your flowcharts and conceal your tables, and I shall continue to be mystified. Show me your tables, and I won’t usually need your flowcharts; they’ll be obvious.

– Fred Brooks

We spend so much time as an industry building tools to…refactor our code, or move the text, or collapse the text…but almost no time solving the actual problem that we need to deal with, which is analyzing our data throughout the whole process.

– Mike Acton

- Table testing

- Database-driven tests

- Snapshot testing

- Fuzz testing

- Spec-generated tests

- AI-generated tests

- Built-in test runners

- Auto-formatters, linters, other static analysis tools

- Code instrumentation for profiling, detection of memory issues, telemetry, etc.

- Structured logging

- Omniscient debuggers

Scrap

Programming culture seems to be obsessed with finding elegant, all-encompassing models. These usually seem to be designed by galaxy-brain tryhards who feel more like they’re trying to sell you a product to lock you into, rather than actual

I want simple, straightforward, intuitive tools that don’t try to do everything and don’t require

Specifically, I think we can do much better when it comes to testing. Rather than chastise developers for not devoting enough time to writing a litany of ad hoc tests, we should instead consider how we can eliminate tedium and streamline the creation of effective test suites.

Let’s take note of some techniques and tools that currently exist:

Although these haven’t gone mainstream yet, I still see immense untapped potential in the “just capture everything” approach, given the right visualization and a well-designed interface. As our storage capacities continue to grow and get even cheaper, this idea becomes more trivial and appealing by the day.

What I propose is an Omnisicient Test Generator. Generating at least 80% of our tests should be as simple as declaring a few “cost-based” assertions along with our usual static types, as shown above. You can think of it like Printf on steroids: it should be just as fast to type, but with a whole lot more payoff.

Whereas static types are checkable assertions about individual values, cost-based types make assertions about the relationships and interactions between values. This could unlock seamless tracking and analysis of not just the code, but any data that flows through it. And unlike static types, the semantics of these cost-based assertions would not have to be tied to the language of the files they are contained in. In fact, language-independence could allow more flexibility, more possibilities, and a unification of the polyglot codebases which constitute many modern systems.

Let’s say this test generator is an app called otg. Here is one workflow I envision:

- Run

otg - Write code as usual, but also write cost-based assertions

otgcreates an instrumented development build with automatic input/output capture- Input/output pairs are serialized and written to tables, either in files or in an embedded database

- As you develop and refactor functions,

otgautomatically tests cost-based assertions against previously captured input/output pairs - Example:

pureordeterministicasserts that the same input always results in the same output - An interface would also allow developer to mark input/output pairs as “verified”

- Custom verification logic can also be written for more specialized tests

- Each function table’s non-verified records are automatically capped and pruned

- Mocks can automatically be generated from input/output tables for “unreliable” functions like API calls

- Generating documentative tests for third-party APIs naturally emerges from simply notating cost-based types for endpoints and using them

- Tests can be “ejected” to standard code-based tests

There are certainly edge cases to consider around how to handle special types of data or code changes, but those are hardly showstoppers. I feel this tool could significantly improve developer quality-of-life, by reducing cognitive load and repetitive drudgework. In turn, this would increase programming productivity and software robustness.

This is what the acolytes of “test-driven development” should strive for: not an antiquated ideological horsewhip, but an advanced exosuit that serves us, instantly providing the information and power we need to enhance our innate abilities. I’ll put my money where my mouth is, and develop a proof-of-concept in what little free time I have. Until then, I’ll leave you on this quote:

– John Carmack